Ahmad Barakizadeh

Ahmad Barakizadeh is an Iranian artist, sculptor, caricaturist, and lecturer. He has been living in exile in Berlin since 2011. In addition to Shiraz in Iran and Caracas in Venezuela, Berlin is a place where he feels at home. He’ll never return to Iran because he is persecuted there due to his political art. He was already a refugee within Iran when he was a child, long before he came to Germany.

Khorramshahr, Iran

Khorramshar; “Our city our home” by MastaBaba is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

Ahmad Barakizadeh was born in Khorramshahr in 1969. This Iranian city lies at the border to Iraq, near Abadan. As the country’s oil production center, Abadan was a prime target in the Iran-Iraq war. Khorramshahr was attacked in 1980 and remained in Iraqi control until 1982. More than 10,000 people died in the conflict. The Barakizadeh family flees the city.

Shiraz, Iran

After leaving Khorramshar, the family settles in Shiraz, at the foot of the Zāgros mountains, about 500 km (300 mi.) away. Ahmad remains in Shiraz until finishing secondary school. Besides going to school, he also draws a lot. He describes drawing as a dialogue with paper that he has been engaging in since his childhood. Even later on, he continues to visit the city and environs since he feels comfortable and at home there.

Ahmad Barakizadeh near Shiraz

Teheran, Iran

Ahmad Barakizadeh in his studio

Ahmad serves in the army for two years starting in 1990. In Tehran he is placed in the language department, where he draws illustrations for English text books. After his military service, he wants to study abroad. In order to save money for his studies, he works as a graphic designer in various Iranian cities, including his hometown of Khorramshahr and Shiraz.

Kharkiv, Ukraine

In 1997, Ahmad goes to Kharkiv, Ukraine, and starts learning Russian. He actually wants to study social psychology, but his language competence is not good enough yet. He studies art (easel painting and sculpture) and in 2005 he completes his master of arts degree from the Kharkiv State Academy of Design and Arts.

Ahmad Barakizadeh next to his MA project

Tehran, Iran

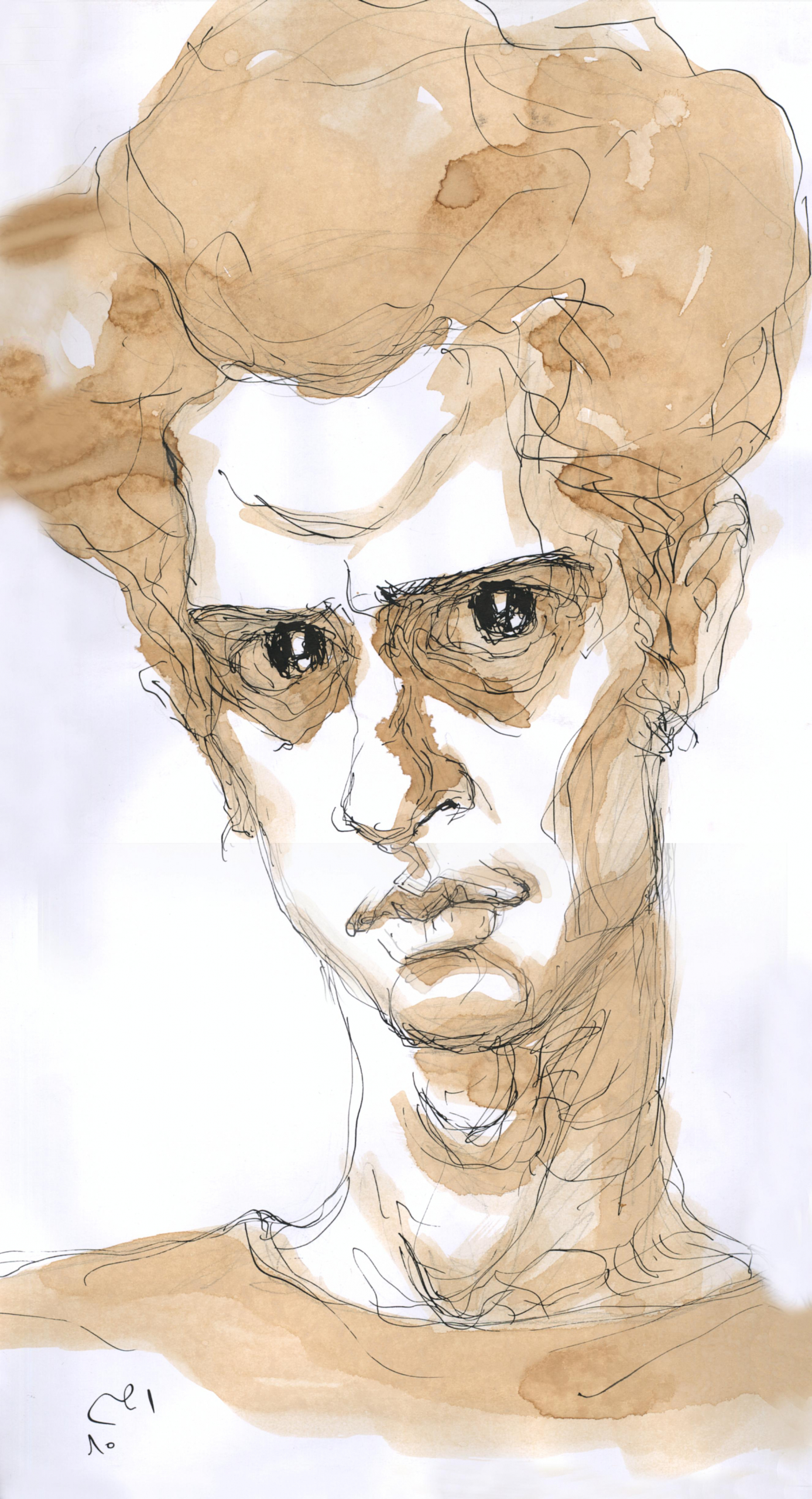

self-portrait

Ahmad returns to Iran in 2006 and works as an artist, a political caricaturist, and lecturer at the University of Tehran’s College of Fine Arts and at the Tehran Art University. As figurative sculpture is banned in Iran, his studio becomes a meeting place for students, so they can nevertheless work freely. After the protests against the Iranian presidential election in 2009, the situation of dissidents worsens. In 2011, Ahmad has to leave Iran.

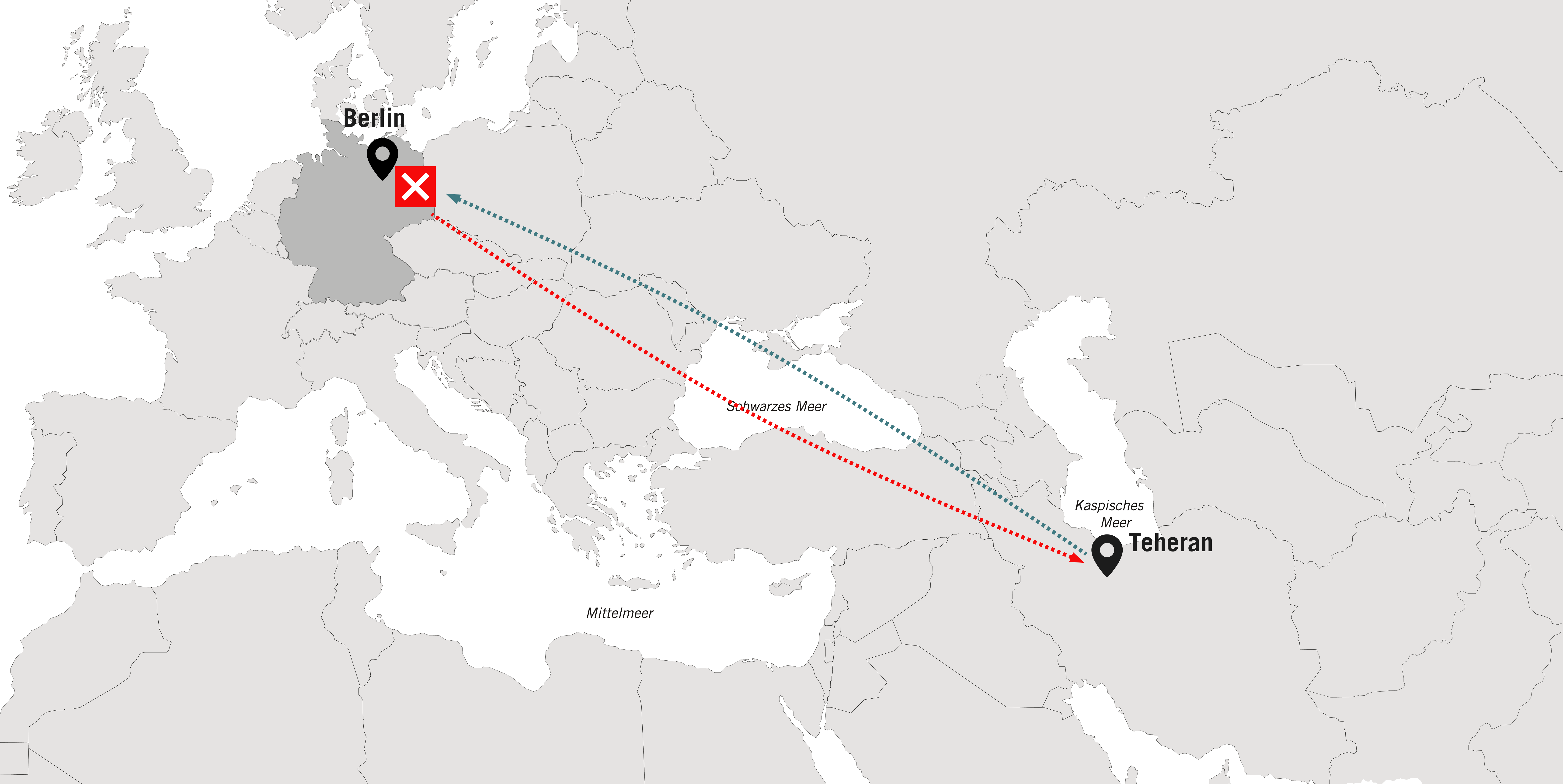

Fleeing from Tehran to Berlin.

Dip pen he took when he left Iran

"I’ve used this dip pen for seven or eight years. I always have it and a USB stick with me. Those are the only things I took with me when I left Iran."

(Ahmad Barakizadeh, 2012)

Berlin

Ahmad arrives in Berlin in August 2011 and files a petition for asylum. After a short stay in a reception facility he moves into housing for single men. The noise and commotion are very stressful. He receives a place in the Marienfelde temporary housing facility, where he stays for two years.

Ahmad Barakizadeh, 2012

Forced Migration, 1 year later

“In answer to the question, if I am happy, I once answered: Personally, I am happy. But can you be happy when so many around you are suffering so much?”

(Ahmad Barakizadeh, 2012)

Forced Migration, 5 years later

Ahmad Barakizadeh 2016

Ahmad receives a permanent residence permit and lives in Berlin-Neukölln. He would like to move to a quieter location, but the conditions of the Social Welfare Office, the tight housing market, and the discrimination he faces makes the search for an apartment more difficult.

Ahmad’s workplace

Ahmad works a lot. He is a freelance sculptor, artist, and conservator. He draws political caricatures for the Kayhan newspaper in London. At the Artothek, a program of the Berlin State Office for Health and Social Affairs (LAGeSo) for promoting artists, he has use of a studio that allows him the space and tranquility he needs for his work.

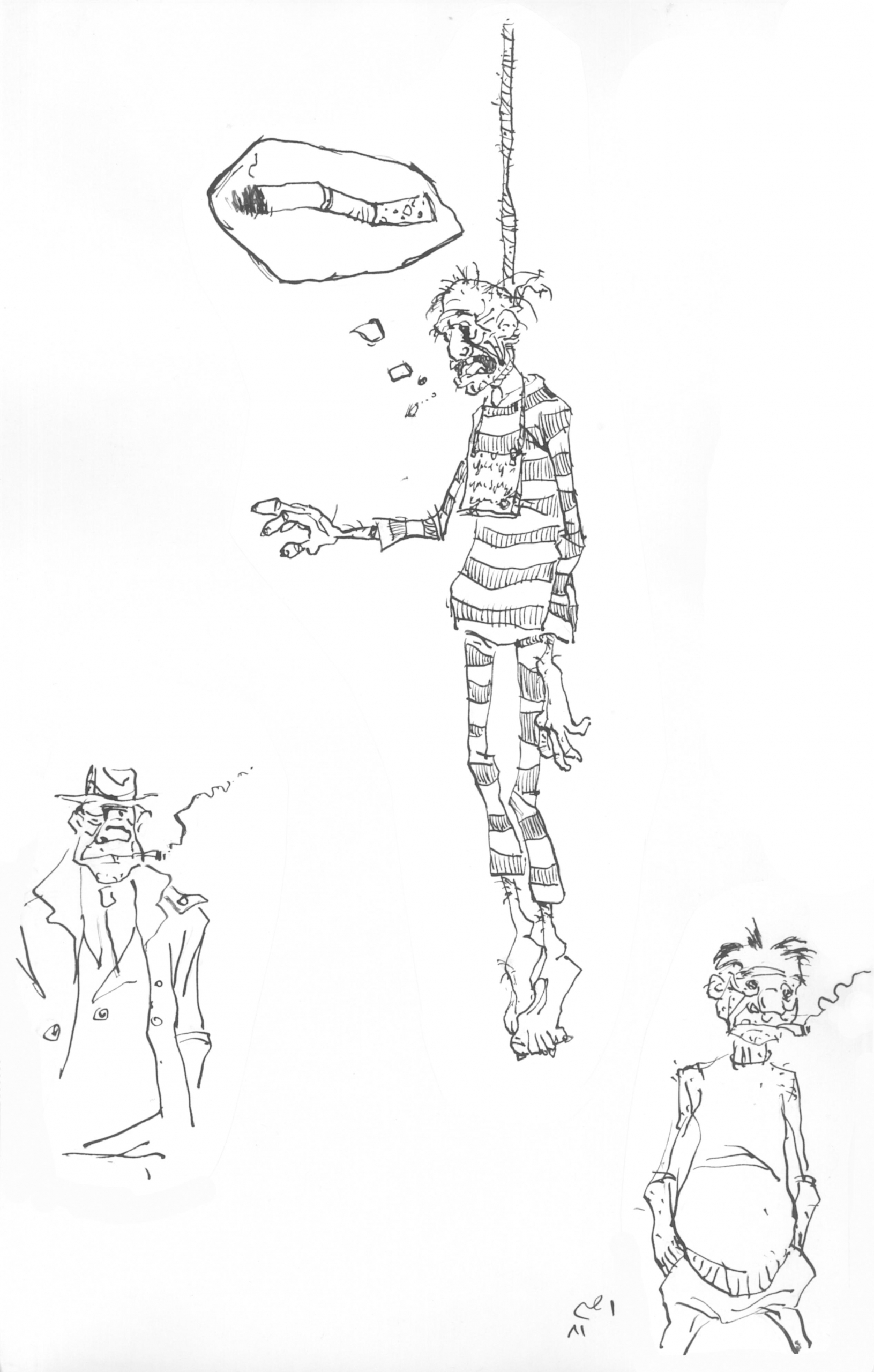

Caricature by A. Barakizadeh

“The world still doesn’t know what is happening in my homeland.”

(Ahmad Barakizadeh)

Exhibition objects

He chooses the dip pen he brought from Iran as an object for the Life after Forced Migration exhibition, for which he also sculpts a stone lion. His design combines ancient Iranian and European forms.

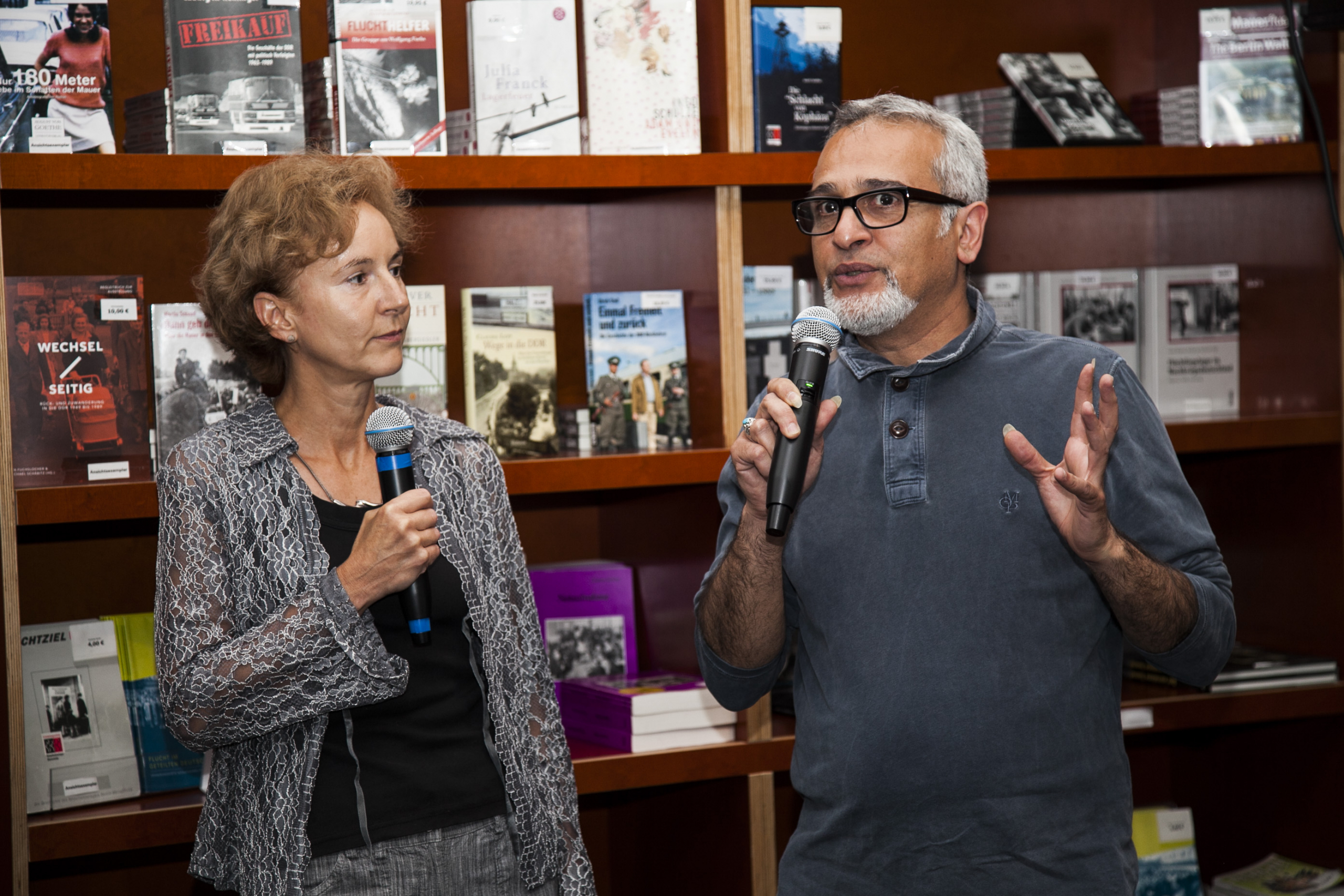

Exhibition opening, Refugee Center Museum, 2017

Ahmad built up a circle of friends through his work, exhibitions, and lectures. He would like to teach again and dreams of opening his own art school.

Ahmad in his studio

“Friendship is one of the most important things in life. We have acquaintances out of necessity and we have friendships that are unconditional. What I appreciate about my friends is that they accept me the way I am. In a world where everything is calculated, it is so valuable when people simply accept each other.”

(Ahmad Barakizadeh, 2016)

Forced Migration, 10 years later

After ten years in Germany, Ahmad wants to become naturalized. As a freelance artist he cannot verify an assured income, so he has been denied German citizenship up to now.

He cannot let go of the situation in Iran. He publishes new caricatures about the political situation in his homeland each week. The Covid-19 pandemic has shattered his dream of opening his own art school in a space he would rent himself.

Ahmad is still living in the apartment he moved into after leaving the temporary housing facility. He has given up seeking a new neighborhood to live in. He finds peace and fulfillment through his work in his studio.

Place of Refuge in Berlin-Marienfelde?

Could Ahmad Barakizadeh have made it to Berlin-Marienfelde if he had fled ten years later?

International air traffic was largely suspended in 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic. However, even earlier it was very difficult for refugees to enter the country by air. In 2019, 50 percent of all Iranian petitions for asylum were rejected within two days directly at the airport (Source: BAMF, airport statistics). In regular asylum proceedings, this is the case in only 2 percent of all Iranian petitions. The disparity in the figures raises the question whether the petitions are reviewed fairly and with sufficient diligence during the airport procedure.