Who is we?

Whether the situation is voluntary or forced, legal or illegal, temporary or permanent: More and more people live outside their country of birth.

Migration has always changed the world we live in. Nation-states, however, see themselves therefore faced with new challenges: In many places, currently valid laws and conventional instruments to shape policies and society no longer correspond to the necessities and needs of a mobile and diverse population.

An important subject is the meaning of citizenship. Does this concept of national affiliation still fit in a time in which many people feel connected to more than one place or country in the world? What about people who live in Germany but do not have a German passport?

A passport, in Germany sometimes called a “national passport,” serves as verification of a person’s identity and citizenship. Everyone who holds a German passport enjoys full civil rights within Germany.

All Germans have a right …

… to decide for themselves where in Germany they want to live.

… to freely choose their occupation, place of work, and place of training.

… to gather peacefully and unarmed without having to register or obtain permission.

… to form clubs and associations.

… to defend themselves against attacks on the democratic order.

… to participate in elections by voting.

… to run for election and be elected.

… to not have their citizenship revoked.

… to not be deported to another country.

A German passport guarantees political participation and security. Anyone who is not German by birth, as the child of German parents or parents living permanently in Germany, can gain German citizenship through naturalization. But the obstacles are great.

Everyone who receives a German passport through naturalization must …

… have been living legally in Germany for at least eight years.

… verify their identity.

… have permanent residence status.

… have independent means of securing a livelihood for themselves and family, without resorting to social assistance payments or Unemployment Benefit II.

... have adequate German language skills.

… have good knowledge of the legal and social system in Germany.

… be committed to the free democratic constitutional order of the Basic Law.

… “be integrated into everyday life in Germany”.

… have a clean criminal record.

… generally relinquish their former citizenship (some exceptions apply).

Passport stories

Citizenship regulates who “belongs” legally and politically, and who does not. But a passport in and of itself does not create a feeling of belonging. Personal experiences play a crucial role. Here, ten people tell us what their passport means to them.

Anas S.

I come from Syria. My Syrian passport was confiscated by the Syrian secret service. I was able to flee with a travel document from the German embassy in Lebanon. This substitute passport saved my life, but it does not grant me the same rights as Germans. This makes it hard for me to plan by future. You need a German passport in order to put down roots here. I would like to vote, since democracy makes it possible to belong. The country should belong to those who take responsibility.

Gülsah S.

I was born as a foreign national in the federal state of Schleswig-Holstein. Until I was sixteen I had a Turkish passport, but I have never lived in Turkey. Before I was naturalized, I was always afraid I would be expelled. My parents were honest, hard-working people. But we lived in an area where many people had a precarious living situation. Armored men once stormed our apartment since they suspected us of counterfeiting. They didn’t find anything, but I was still afraid I would have to leave Germany. Without a German passport I always felt like I was someone who wasn’t actually allowed to be here. Every time I traveled to Turkey I was afraid I would never see my home again. Now I have a German passport and I use it for all my travels.

Christian Z.

I was born in Germany and my ancestors also came from here. As a citizen I have all political and social participation rights. For my sense of belonging, though, it is more important that I have access to free education and social benefits, and that I live in a country under the rule of law. Although Germany offers all that, I often view the state and politics critically. I get involved for a society in which the common good and human rights are what guide everyone’s actions.

Joshua F.

I was born and raised in Germany. My father is a Black American, who as a soldier was stationed in Germany. I have never lived in any other country as long as I have lived in Germany. The center of my private and professional life is clearly here. But I don’t always feel accepted as a member of society. Especially in rural areas I am often asked here I come from. When I say “Bremen” in response they usually then ask about my “real origins.”

Shuah B.

I have both German and American citizenship from birth. I was born in Berlin and went to school here; I studied in Germany and I work here. I view myself primarily as a German citizen, but I also feel very closely tied to the American language and culture. In Germany I feel accepted but sometimes people ask about my heritage because of my name. I often travel to friends and relatives in the United States and I exercise my right to vote in elections there.

Marina L.

I come from Brazil. I came to Germany after my university studies in 2007. I didn’t receive an unlimited work permit until 2013. I applied for naturalization in 2016. I had to verify my financial independence and pass language and civics tests. Eight months after applying, my naturalization was approved. Since 2016 I have been a German citizen and I work as a teacher. I feel very good in Berlin and have made a lot of close friends.

Alex T.

I was born in Germany and I have German citizenship. I have been living in London since I was 21. I primarily feel like a Londoner, but also like a German and European. Since Brexit a lot has changed for me. Although I am married to a British woman, it was not clear whether I could stay. Meanwhile I also have British citizenship. It was a difficult, drawn-out process. I would never have given up my German citizenship.

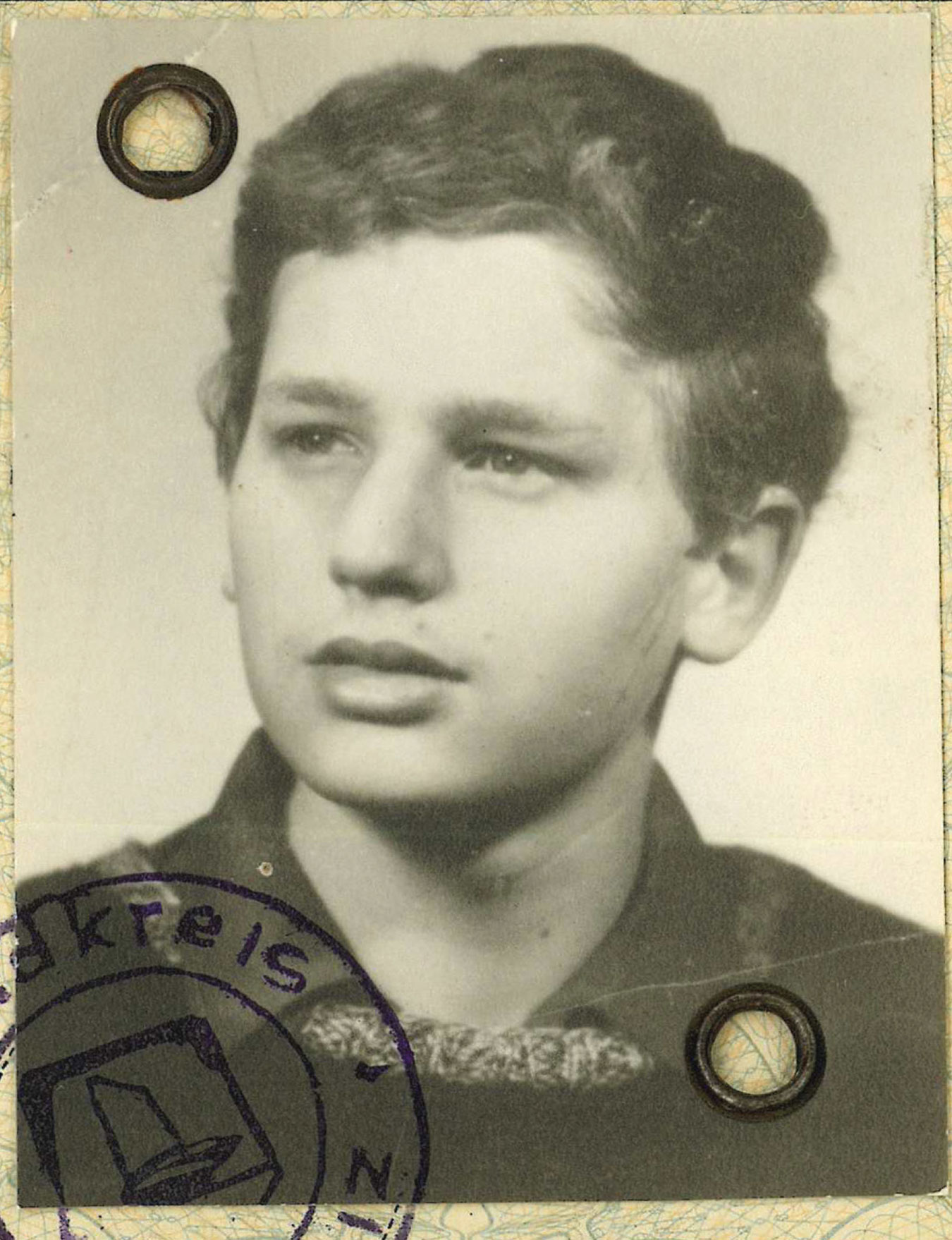

Thomas F.

I was born in East Germany in 1955. As a teenager I had problems with the strict limits set by the East German dictatorship. I wanted a self-determined life and freedom of opinion. That is why I decided to flee to West Germany. My cousin in the West procured a passport for me, on which he forged stamps and attached a new photo. I managed to flee under the name Philip R. in July 1974. In the West I received a new passport without any problem – this time with my real name.

Tatjana W.

I was born in the Soviet Union, in Siberia to be exact. As a Volga German, my mother had been deported there in 1941. In my childhood people called us “fascists.” Later, no one knew anymore about my German roots. I was content with my life, but in 1994 my mother wanted to follow our relatives to Germany. The first few years here were tough. For a long time I felt like a Russian. As some point I stopped renewing my Russian passport, but I am still saving my first German passport.

Mahmoud S.

I was born in Syria. I lived there until I fled in 2015. I never had Syrian citizenship. My parents fled from Palestine to Syria in 1948. Like them, I have a Syrian passport for Palestinian refugees. I nevertheless felt accepted as a member of Syrian society. In my German passport substitute it says “uncertain citizenship.” I consider that an empty space that hurts. I do have a heritage.

Who can participate in politically shaping Germany?

Who is formally recognized as a member of a society is part of a constant process of negotiation. In Germany as elsewhere, there is controversial discourse about who belongs here and who does not. Those who regard the German community as being determined only by German ancestry, language, and culture view migration first and foremost as a problem and threat. For those who are open to diversity and change, migration is a normal part of society, which must be shaped jointly by everyone.

Voting rights without citizenship

THE IDEA

It is not citizenship but one’s main place of residence that determines the entitlement to voting rights.

THE REASINING

As stakeholders, all people who are subjected to the laws of a country must be permitted to have a say in determining them.

Some countries grant voting rights even to people without the respective citizenship. In New Zealand, for instance, people who have lived there legally for at least one year can participate in national elections. In Chile, five years of legal residence is required, in Malawi seven, and in Uruguay fifteen. In half of all the member states of the European Union, some people can vote at local or regional levels in their country of residence even if they are not EU citizens. In Germany, however, only EU citizens can vote in local elections where they live in Germany.

Urban citizenship instead of national citizenship

THE IDEA

The idea: Everyone who lives in a city has the same rights, regardless of origin, nationality, or residence status.

THE REASONING

With urban citizenship, undocumented people (sans papiers) are better protected against deportation, exploitation, and discrimination.

A model for urban citizenship is New York City, where the IDNYC was introduced in 2015. In Europe as well, there are a number of initiatives and cities that are working on an urban citizenship. In Switzerland, the city of Bern started testing such a City Card valid within the city limits in 2021. It makes it easier, for example, for people without an official residence permit to sign contracts such as rental agreements or mobile phone contracts, to take care of banking transactions or doctor’s appointments, or to register their children for daycare. They do not need to fear getting deported when visiting government offices, coming into a police checkpoint, or if they want to report a crime.

Who can help shape Germany politically?

Can a passport be the only condition for political participation in a democracy, or do all people who live here need to be entitled to this right?